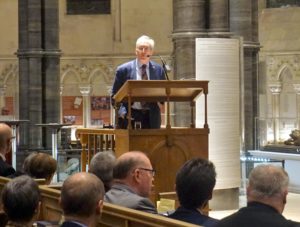

Professor Diarmaid MacCulloch delivers the Lyndwood Lecture 2018

November 9, 2018

Professor Diarmaid MacCulloch more than lived up to his reputational promise in delivering Richard Hooker (1554 – 1600): Invention and Re-invention at the  Temple Church on 7 November.

Temple Church on 7 November.

It was an altogether splendid presentation and not the first distinguished lecture to be given on Hooker in his church with the ELS (Rowan Williams, 2005). MacCulloch traced for us Hooker’s invention by his gradual departure from Tudor theological orthodoxy in his subtle development of the theology of justification. Hooker, moderate, courteous and cautious, was well aware of his observant and literate critics (the Puritan divine Walter Travers was Lecturer at the Temple Church when Hooker was Master). But in this, he moved away from Calvinism in the most sensitive of all Reformation debates. In addition, he understood the church in a sacramental way. While continuing to stress ‘reception’ in terms of the eucharistic presence he articulated a strong sacramentalism and moved away from the word-based ‘sermon’ ecclesiology of the Elizabethan Church. He had significant supporters in Archbishop Whitgift in opposing the Puritans and in Bishop Lancelot Andrewes. Hooker’s ‘new’ theology would have suited the Queen, as it certainly did later for James I/VI and Charles I. In this Hooker charted a different path from Continental and Scottish Protestantism which became a distinguishing mark of what was later to become Anglicanism. Nor was the Pope Anti-Christ, he might even be a Patriarch.

But the later Laudian revival of liturgy and sacramentalism did not mean every aspect of Hooker’s invention was canonised. Hooker also taught that Kings ruled by covenant and consent rather than by the Divine Right claimed by the House of Stuart. Though he did cogently argue against Presbyterianism as of Dominical institution, he did not conversely argue that episcopacy was de jure divino. The Continental Protestant Churches were real ‘church’. Was this the reason the later parts (books 6, 7 and 8) of the Laws of Ecclesiastical Polity were only published much later in the 17th century? Be that as it may, Hooker’s avoidance of Scriptural fundamentalism in ecclesiastical polity and his stress on the organic nature of church and ministry remains an Anglican characteristic, even if some later Anglicans have argued otherwise. His stress on the role of reason was also significant for later Latitudinarianism.

With the Restoration of the Monarchy and the Church of England, Hooker became sanctified through the biography of Izaak Walton, though more hagiographical than historical. With the Tractarians, reinvention continued, John Keble editing a critical edition of the Laws in 1836. Though important, Keble’s comments and footnotes are sometimes a partial reading.

With the Restoration of the Monarchy and the Church of England, Hooker became sanctified through the biography of Izaak Walton, though more hagiographical than historical. With the Tractarians, reinvention continued, John Keble editing a critical edition of the Laws in 1836. Though important, Keble’s comments and footnotes are sometimes a partial reading.

MacCulloch left the two Societies (the ELS and the Canon Law Society of Great Britain and Ireland) with a tantalizing glimpse of Hooker’s relevance for current Anglican debate. Behind the specific questions on human sexuality, there lie deeper issues of authority. Is Scripture a set of prescriptive rules or can the Church discern with reason and consent as well as Scripture? On a lighter note, despite the praise of Hooker found in the Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church for his ‘masterly English prose’, MacCulloch was not an admirer of his complex syntax! But praise must be given for MacCulloch’s clarity and dynamic exposition.

Though today, all schools occasionally claim Hooker, MacCulloch ended with the certainty that no-one has the last word on him!

+Christopher Hill